Nurduran Duman* has translated two stories of mine

(The tiger and the mice and Sweat, Joy, and Thunderation)

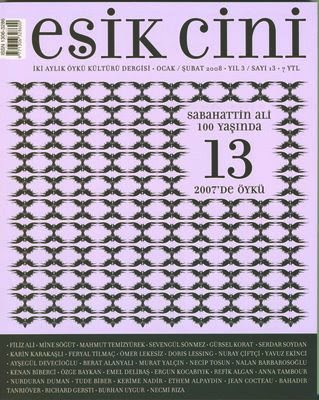

and also interviewed me and translated that for the current issue of this Turkish magazine.

I usually frown on interviews of creative types - all kinds of artists and interpreters such as actors - because interviews make the person the interest, and worse. Interviews implant the interviewee with the urge to explain the 'work', thereby killing the 'work' while the interviewee, that clear-eyed parasite-ridden zombie, lives on to explain again.

However, and of course, my interview is delightful, especially as it's so exclusive (only a hundred million people might be able to read it). Nurduran Duman's questions were so thoughtful and unexpected that she got me saying things I never thought I would - and my creations didn't even utter a squeak. But I might kill one of those stories now by explaining it to you in confidence. Please don't tell Nurduran. I don't want to spoil the interview.

The tiger and the mice, posted earlier on this blog, was written to respond to a certain privileged person from another country. He complained to me about the repressions his country puts himself and his family through (those who haven't escaped to a land-of-the-free) but he also bombarded me with his government's "right of reserving any military means to smash" those they want to keep from the freedom that he complains he doesn't have. I am particularly pleased that Nurduran chose this tiny fable to translate. The wish for freedom is as universal as the determination to kill its very thought.

The real of course about all this is the amount that Nurduran Duman taught me about what I not only don't know but never thought about, such as Turks and haiku; and the spelling, Turkey, being "a 'bad joke' by some English people in the past. Especially it bothers us in December."

So -

TÜRKÝYE or TURKIYE, please - but which one where?

As for the language,

Turkish ... is a member of the Turkic family of languages, spoken by well over a hundred million people ... Anyone interested in languages should enjoy seeing how Turkish speakers clothe the ordinary human thoughts and feelings in a completely new garb.

- Geoffrey Lewis, Teach Yourself Turkish, Hodder and Stoughton, London, 1989

Finally, I hope someone comments on the title of the magazine, which is much more intriguing than anything about or by me. It's time that many more works in Turkish were translated into other languages. And although some tales have been translated, Turkish folklore is long past-due to be part of well-known worldlore, for it's so rich.

* Nurduran Duman is a pretty fascinating character. A prize-winning poet, fiction and non-fiction writer, editor, radio personality, and naval architect and ocean engineer.

(The tiger and the mice and Sweat, Joy, and Thunderation)

and also interviewed me and translated that for the current issue of this Turkish magazine.

I usually frown on interviews of creative types - all kinds of artists and interpreters such as actors - because interviews make the person the interest, and worse. Interviews implant the interviewee with the urge to explain the 'work', thereby killing the 'work' while the interviewee, that clear-eyed parasite-ridden zombie, lives on to explain again.

However, and of course, my interview is delightful, especially as it's so exclusive (only a hundred million people might be able to read it). Nurduran Duman's questions were so thoughtful and unexpected that she got me saying things I never thought I would - and my creations didn't even utter a squeak. But I might kill one of those stories now by explaining it to you in confidence. Please don't tell Nurduran. I don't want to spoil the interview.

The tiger and the mice, posted earlier on this blog, was written to respond to a certain privileged person from another country. He complained to me about the repressions his country puts himself and his family through (those who haven't escaped to a land-of-the-free) but he also bombarded me with his government's "right of reserving any military means to smash" those they want to keep from the freedom that he complains he doesn't have. I am particularly pleased that Nurduran chose this tiny fable to translate. The wish for freedom is as universal as the determination to kill its very thought.

The real of course about all this is the amount that Nurduran Duman taught me about what I not only don't know but never thought about, such as Turks and haiku; and the spelling, Turkey, being "a 'bad joke' by some English people in the past. Especially it bothers us in December."

So -

TÜRKÝYE or TURKIYE, please - but which one where?

As for the language,

Turkish ... is a member of the Turkic family of languages, spoken by well over a hundred million people ... Anyone interested in languages should enjoy seeing how Turkish speakers clothe the ordinary human thoughts and feelings in a completely new garb.

- Geoffrey Lewis, Teach Yourself Turkish, Hodder and Stoughton, London, 1989

Finally, I hope someone comments on the title of the magazine, which is much more intriguing than anything about or by me. It's time that many more works in Turkish were translated into other languages. And although some tales have been translated, Turkish folklore is long past-due to be part of well-known worldlore, for it's so rich.

* Nurduran Duman is a pretty fascinating character. A prize-winning poet, fiction and non-fiction writer, editor, radio personality, and naval architect and ocean engineer.

No comments:

Post a Comment